O'Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism

Backed by Marquette University, the O'Brien Fellowship program helps news professionals dig deep while mentoring student journalists.

The program honors Marquette alumni Alicia and Perry O'Brien. Their daughter, Patricia Frechette, and her husband, Peter, donated $8.3 million in 2012, to create the fellowship. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel is a co-founder and partner.

The O’Brien Fellowship accepts applications from journalists using print, digital, or visual mediums. Applicants may also produce news or opinion content. Journalists producing opinion content, however, including editorial writers and columnists, should inform, and support, their views and commentary with independent, in-depth investigative reporting.

Learn more

A Unique Journalism Fellowship

- Report and produce an in-depth public service journalism project on a regional, national or international topic.

- Receive a $75,000 salary stipend and additional support.

- Fellows traditionally are in residence, but we are now taking remote or partial remote applications along with full-residency arrangements. The O’Brien newsroom is housed at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication near downtown Milwaukee and the Lake Michigan shore.

- Publish or broadcast the project through your home news organization or, in the case of independent journalists, another outlet.

- Integrate Marquette’s best journalism students into your projects as reporters and researchers.

- Help identify a journalism student for a university-funded summer internship at your news organization or other publisher.

Marquette University challenges students and staff to Be The Difference by working with the community for the greater good. Marquette, as a Catholic, Jesuit institution, has educated journalists for more than 100 years with this mission.

Learn more

Student Fellow Published Three Months Into Fellowship

Mia Thurow, an O’Brien Fellowship student intern for 2025-26, is a third-year student majoring in journalism with a minor in Spanish and a concentration in communication leadership. She currently serves as Executive News Editor at the Marquette Wire and previously worked at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel as a McBeath summer intern. She is passionate about investigative and human interest storytelling, and she hopes to help create a more representative media landscape where all voices are heard.

This year, Mia is working with Detroit-based writer and O’Brien Fellow Eddie B. Allen Jr., a published author and award-winning reporter. An independent journalist, he often writes about wrongful convictions and criminal justice issues. He is an advocate for social justice and the president of the Urban Solutions Training & Development Board of Directors. Mia particularly enjoys working with Eddie because of his profound perspective on life, his extensive journalistic experience, and his sense of humor — quite possibly her favorite trait of his.

Alongside Eddie and O’Brien student interns Sofie Hanrahan and Reyna Galvez, Mia is working on “Exploring Integrity: Reviewing Wrongful Conviction Remedies,” a series examining the impact of conviction integrity units on the American judicial system’s rate of wrongful conviction. Her first story, published in the Detroit Metro Times on Nov. 19, explores attorneys’ opinions on the possibility of a conviction integrity unit in Wisconsin, a state where no such unit exists. During the reporting process, she enjoyed hearing a variety of opinions from attorneys with vastly different experience levels. She looks forward to continuing to explore wrongful conviction remedies throughout the rest of her time with the O’Brien Fellowship.

Washington Post reporters Dana Hedgpeth (left), Sari Horwitz (right), and The Post staff have won the 2025 Dori J. Maynard Justice Award for “Indian Boarding Schools,” a searing five-part series based on an 18-month investigation of the widespread sexual abuse of Native American children by Catholic priests, brothers, and sisters. Judges called the entry haunting, beautifully done, and probing.

The Dori J. Maynard Justice Award, sponsored annually by the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University in Milwaukee, honors social justice reporting that illuminates ignorance, systemic racism, intolerance, negligence, and inequality.

This is the second straight year The Washington Post has won the Dori J. Maynard Award. One of 10 Poynter Institute Journalism Prizes, the award honors the memory of Dori J. Maynard, a former ASNE board member and advocate for diversity in journalism and newsrooms. The award comes with a cash prize of $2,500.

Contest winners are expected to visit Marquette University this fall, in person or virtually, to present their series as part of the Burleigh Media Ethics Lecture series.

"This work represents the best tradition of public service journalism, the legacy of Dori J. Maynard, and the mission of the O'Brien Fellowship to promote justice and equality," Jeffery Gerritt, director of the O'Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism, said Monday. "It illuminates a shameful chapter in U.S. history that continues to traumatize Indigenous peoples. We're honored to welcome to Marquette the journalists who produced this outstanding work."

The United States government operated Indian Boarding Schools, where thousands of students died, for roughly 150 years, from 1819 to 1969. Last year, U.S. President Joe Biden apologized to all Indigenous Americans for the harm caused by federal Indian boarding schools that separated Native children from their families and tribal communities.

Hedgpeth, a Native American journalist who has worked for The Washington Post for 25 years, is an enrolled member of the Haliwa-Saponi Tribe of North Carolina. She has covered Native American issues, Pentagon spending, and the U.S. Defense industry, as well as local governments, courts, and rail and bus systems. Her honors include the Gerald Loeb Award for Best Writing with Post colleague Robert O’Harrow Jr.

Horwitz, an investigative reporter who covers criminal justice, has won numerous national awards. She shared in four Pulitzer Prizes for coverage of the child welfare system, police shootings, the shooting rampage at Virginia Tech, and Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election.

Horwitz is the author of the series “Justice in Indian Country” and co-author of the book “American Cartel: Inside the Battle to Bring Down the Opioid Industry.”

Full winning entry:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/interactive/2024/sexual-abuse-native-american-boarding-schools/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/interactive/2024/american-indian-boarding-schools-history-legacy/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/interactive/2024/native-american-deaths-burial-sites-boarding-schools/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2024/10/25/biden-apology-indian-boarding-schools/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2024/06/14/catholic-church-indian-boarding-schools/

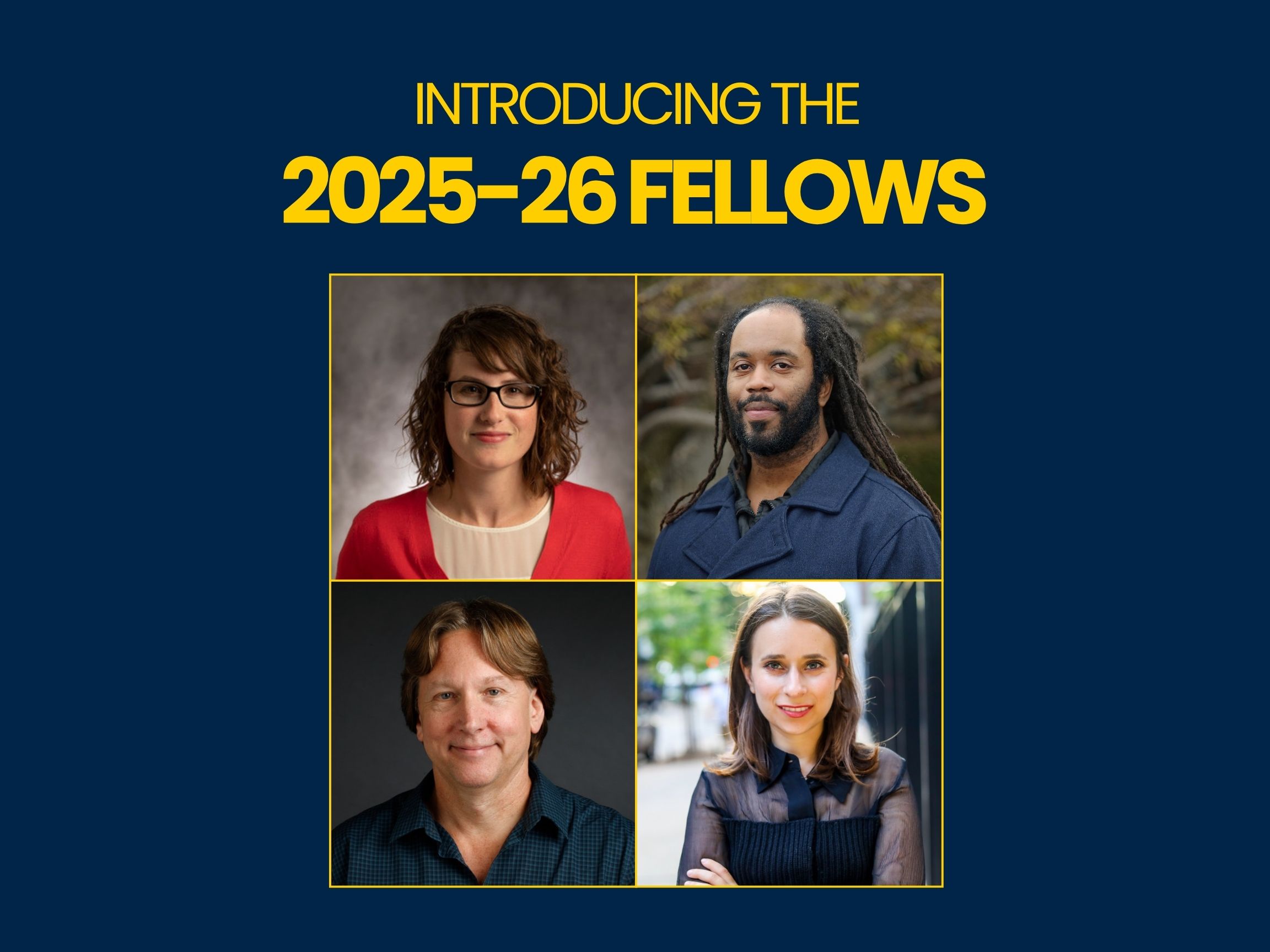

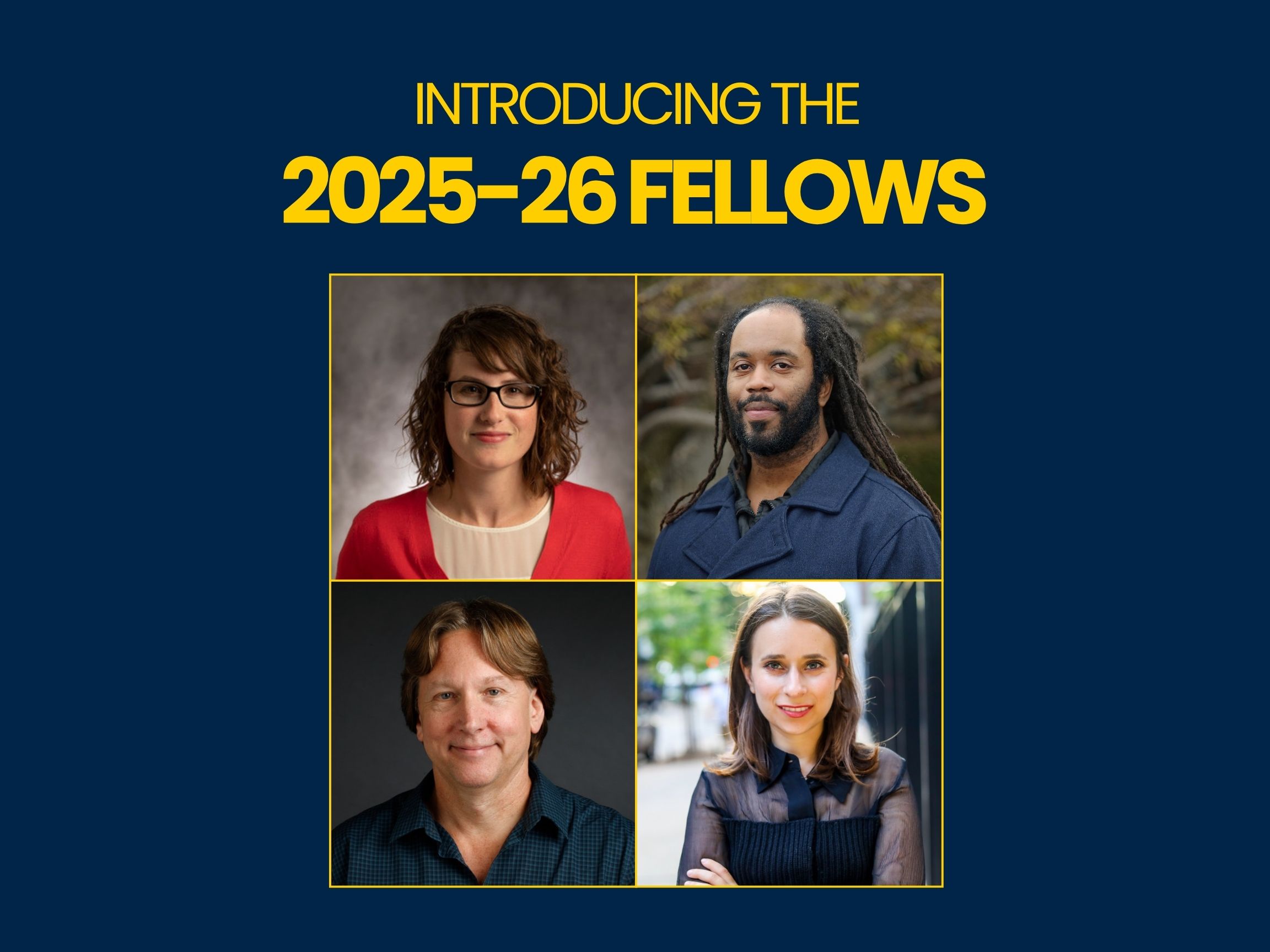

Four renowned journalists receive O’Brien Fellowships

The O'Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism in April awarded investigative reporting fellowships to four nationally renowned journalists: Eddie B. Allen Jr. of Detroit, Britta Lokting of New York City, Miles Moffeit of Milwaukee, and Alison Dirr of Milwaukee. They were selected from among more than 60 entries, the deepest applicant pool in O’Brien’s 13-year history.

Allen, Lokting, Moffeit, and Dirr will each receive $75,000, with additional stipends for research, travel, and housing, to complete in-depth journalism projects that will advance justice and equity on local and national issues. Their nine-month Fellowships, running from August of 2025 to May of 2026, will focus on wrongful convictions, police misconduct, hazardous lead, and discrimination against parents with disabilities.

"These four award-winning journalists are among the nation’s best,” O'Brien Director Jeffery Gerritt said. “Their ground-breaking, multi-media projects will, not only expose injustice, but also propose solutions to those problems.”

Throughout his decades-long career, Moffeit has focused on civil rights and criminal justice issues. A former special projects reporter for the Dallas Morning News, Denver Post, and Fort Worth Star Telegram, Moffeit was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting. He served as a senior Ochberg Fellow with the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia Journalism School.

Moffeit’s O’Brien project will examine the lack of accountability for police misconduct, sometimes leading to tragic results.

Lokting, an independent journalist, has written and reported extensively on overlooked, rural, and Western communities. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian, and many other media outlets.

A multiple award-winner, Lokting was a 2023 journalism fellow with the Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics.

In her O’Brien project, Lokting will examine how certain states curtail the parental and custodial rights of people with disabilities, often for arbitrary reasons. During her fellowship, she will move from New York City to Milwaukee.

Throughout his 30-year career, Allen, an independent journalist, author, and former newspaper reporter, has exposed dysfunctions in the criminal justice system, revealed wrongful convictions, and covered national figures such as President Bill Clinton and Rosa Parks. He has written for, among others, the New York Times, Associated Press, BET, Detroit Free Press, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Metro Times, and Toledo Blade.

Allen is independently producing his first biography, “Low Road: The Life and Legacy of Donald Goines” (St. Martin’s Press, 2004) as a feature film. In his most recent book, “Our Auntie Rosa (Penguin/Random House, 2015), Allen collaborated with the family of civil rights icon Rosa Parks. Allen is president of the Urban Solutions Training & Development Board of Directors.

Allen’s O’Brien project will examine the national problem of wrongful convictions, using a new Conviction Integrity Unit in Detroit to dissect how criminal investigations can go awry and propose ways to prevent and reverse them.

Dirr, the City Hall reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, has covered a variety of beats in her dozen years of daily reporting in Wisconsin, including frac sand mining, police and courts, and municipal government.

Most recently, Dirr has reported on the implications of the local government funding law known as Act 12, the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, and the U.S Presidential races.

Dirr’s O’Brien project will look at how lead poisoning affects the health and lives of Milwaukee residents, especially those living in older, poorer sections of the central city. Dirr will examine the effectiveness of Milwaukee’s efforts to alleviate lead poisoning and abate lead paint hazards, especially for local children.

The Latest O'Brien-Backed Journalism

-

Vacancies at Milwaukee Public Schools

-

The Right to Read

-

The Flight of Banks

-

A New Prescription

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Rory Linnane examined vacancies at Milwaukee Public Schools, how they impact students, and how to solve them. Marquette Students Gabriel Sisarica and Chesnie Wardell collaborated with Linnane on the series

The first installement of the series was published in February 2025. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel story addresses the staff vacancies at Milwaukee Public Schools and the impact of those vacancies. A Journal Sentinel analysis found that the vacancies dispropotionately affect students with disabilities, Black students and students from low-income families. With around 11% of staff positions being unfulfulled at any time, MPS expects to save about $70 million that can be spent elsewhere.

The second installment, published in March 2025, investigated how MPS failed to monitor lead paint hazards likely resulting in the lead poisoning of a Milwaukee student. With budget cuts and staff vacancies, the distrcit has fallen behind on maintenance. The district plans to complete inspections of its oldest buildings by the end of May, and additional schools to be inspected after that.

The third installment, published in May 2025, analyzed why hundreds of MPS staff left in recent years and reported how the school district is responding.

Works published to date:

February 20, 2025

Milwaukee Public Schools saves millions on vacant jobs. It balances the budget, but students pay the price.

March 26, 2025

Milwaukee Public Schools lost control of widespread lead paint hazards. Here's how it happened.

May 1, 2025

We analyzed why 887 staff left MPS in recent years. Here's what they said.

Hundreds of staff have told MPS why they resigned. What is the district doing to respond?

O'Brien Fellow Sarah Carr investigated reading disparities in schools and the actions people are taking to close them. This series breaks down how these disparities often play out through a child's life and what approaches are being taken to change that narrative.

Photo by Jahi Chikwendiu / THE WASHINGTON POST

O'Brien Fellow Sari Lesk investigated the struggles that Milwaukee entrepreneurs, many of them racial minorities, face when trying to access funding to start or scale their business. Many small business owners said they found themselves rejected by traditional banks.

Photo by Kenny Yoo / MILWAUKEE BUSINESS JOURNAL

O'Brien Fellow Guy Boulton investigated the social determinants of health across the country, including here in Milwaukee. The story breaks down how social services can be more important to health than access to medical services despite the U.S. health care system accounting for a fifth of the economy.

Photo by Mark Hoffman / MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL